![]() Guide: Vocal Music in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods

Guide: Vocal Music in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods

Historians often point to the Medieval period as the beginning of the unbroken tradition of notated (written down) Western music that developed into what we now consider “classical” or “art” music. Although the earlier Ancient music of Greece was very important and influential, only a few fragments of Ancient Greek music have survived. The Medieval period lasted from the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century (specifically 476 AD) through roughly the 15th century.

It was in Medieval cathedrals and abbeys that explorations of the nature of pitches and rhythms began evolving into what would become the practices of composing and performing standardized much later in the 18th century. Important technical tools such as written musical notation and solfege (a method for sight-singing) also first appeared in the Medieval period. Music with increasingly sophisticated counterpoint–simultaneous melodic lines–began appearing in the 1100s.

The following centuries after the Medieval period saw new developments in musical style, and Renaissance style reached its peak during the 16th century with the music of Palestrina and Lassus.

Tastes and ideas eventually changed and composers like Claudio Monteverdi paved the way for the new Baroque style of music, which began in the 17th century.

While there were a lot of different musical styles during the Medieval and Renaissance periods, there was a clear continuity of musical forms and similarities in the way that people composed, performed, and listened to music during this entire period.

Vocal Music

Instrumental music was popular in the Medieval and Renaissance periods in the contexts of out-of-doors dancing, lords’ banquets, town festivals and ceremonies, popular songs, etc. The surviving documentation of instrumental music is unfortunately not very good, partly because music notation from this time isn’t always very specific about what instrument or voice should be performing a musical part. A lot of instrumental dance music was also learned and passed on orally—that is, by ear rather than by writing—so we don’t know exactly what it was like.

Vocal music held an important position in the Catholic church, which was the dominant cultural and political force in Western Europe, and many of the most highly respected composers specialized in vocal music. On the whole, instrumental music wasn’t considered as worthy of development in the church as vocal music was until, arguably, the late 1500s-early 1600s, with the beginning of the Baroque period.

For these reasons, vocal music is a good focus of study to trace important developments in music during the Renaissance and before, although a consideration of instrumental music during this time is important for a complete understanding of the history of music.

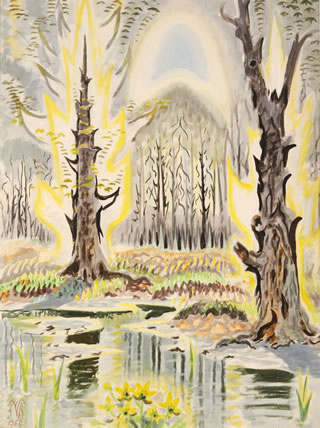

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) is among the most noted American painters of the 20th century. She is well known for her abstracted images of flowers and her images of the New Mexico southwest scenery, which she loved and thrived in for the latter half of her life.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) is among the most noted American painters of the 20th century. She is well known for her abstracted images of flowers and her images of the New Mexico southwest scenery, which she loved and thrived in for the latter half of her life. To create one’s own world, in any of the arts, takes courage.

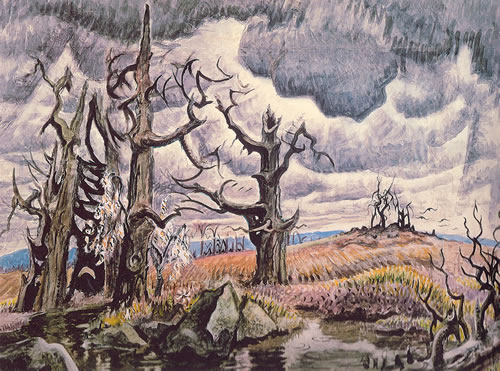

To create one’s own world, in any of the arts, takes courage. The Course of Empire (2008)

The Course of Empire (2008)