![]() Guide: Modern Dance in America

Guide: Modern Dance in America

DANCE IN PROFILE: Alvin Ailey, Revelations (1960)

With Revelations, dancer-choreographer Alvin Ailey (1931-1989) revolutionized the role of African-Americans in Modern dance and created an enormously successful fusion of widely accessible style and themes and artistic quality. Revelations draws on black vernacular culture (derived from what Ailey called the “blood memories” of his childhood in Texas); spirituals, gospel, and blues music; and the precision and virtuosity of “heroic” Modern dance.

Revelations is the most widely-seen piece in the Modern dance repertoire (seen by over 23 million people, according to this page). The dance has been performed at multiple presidential inauguration galas and cited by Oprah Winfrey as something “every American” owes it to themselves to see. Mattel even produced a Revelations “Barbie” doll based on former Ailey Artistic Director Judith Jameson’s design! There is a wealth of information about this piece at the official Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater website.

I was fortunate enough to see Revelations performed live in Boston on April 28, 2012 by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. The company, founded by Ailey in 1958, continues to perform seminal works from Ailey’s repertory as well as the work of contemporary choreographers who continue in his spirit. Robert Battle was appointed Artistic Director of the company in 2011.

It is interesting to note that the original version of Revelations premiered in 1960 utilized six dancers and lasted over an hour, while the current version is performed with more than twice as many dancers and lasts about 40 minutes. Costumes and scenic lighting have also changed over time. The piece currently in performance certainly doesn’t seem dated, as the enormous enthusiasm of the Boston audience attested (which, incidentally, had a strong representation from every age group).

Revelations consists of three sections, each of which contain three or four numbers: first, “Pilgrim of Sorrow” alludes to the atmosphere of oppression in the south and a search for deliverance through spirituality; second, “Take Me to the Water” evokes baptism and a sense of hope and renewal; and third, “Move, Members, Move” consists of exuberant, high-energy numbers conveying church and community.

In addition to the personal love that the composer and his dancers clearly have for the material, the appeal of Revelations can be attributed in part to the combination of the excitement of the gospel music and beautifully composed group dances in numbers such as “Wade in the Water,” [view clip] “Sinner Man,” [view clip] and “You May Run On” [view clip]; the nuanced, controlled, and virtuosic expressions of yearning and aspiration seen in the duet “Fix Me, Jesus” [view clip] and solo “I Wanna Be Ready” [view clip]; and the structural clarity of the sequences of movements and the elegant, simple body shapes–both relaxed and clear–showcased in the opening number, “I Been ‘Buked” [view clip].

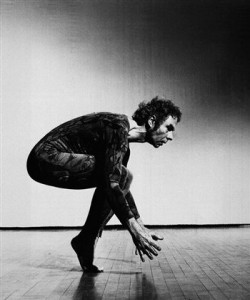

There were a number of stand-out moments in the April 28th performance. The delicate male solo “I Wanna Be Ready” [view a video from a 1986 performance] was performed with outstanding control and strength by Michael Francis McBride. The dancer uses the floor of the stage in surprising and captivating ways, alternately defying and giving in to gravity. The dancers propels himself off the floor while never leaving it: laying on the ground he suspends his hips off of the floor, then reaches his torso and legs outwards in a tight V-shape; he stands up, falls back to the floor, then glances back up at heaven. There is a clearly communicated sense of struggle combined with a representation of divinity and strength in the human form, which beautifully articulates the somewhat mournful solo vocal.

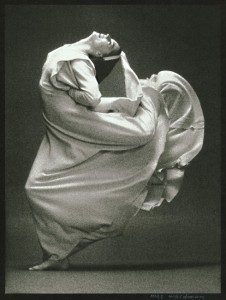

In “Wade in the Water,” [view clip] rhythmically propulsive music is paired with steady, determined movements in which the dancers flex and bend their torsos, leaning back and rolling their shoulders, creating a sense of barely contained energy simmering beneath the surface. Large blue cloths rippling along the floor suggest the river in which a baptism is taking place: a not-so-subtle yet effective device, which provides a clear sense a scene. The soaring leaps, spins, and plunges in the male trio “Sinner Man” [view clip] were thrilling, bringing to mind the athleticism of classical ballet.

Throughout, Ailey has the dancers clearly articulate the phrases, gestures, and forms of the music. The dancers are dancing to the musical score, not alongside or against it, and this mimicking of music brought to my mind the choreographed spirituals of Helen Tamiris. However, Ailey was able to achieve a far more substantial and cohesive expression of that music. The dancing in Revelations is both inevitable-seeming yet spontaneous; intuitive yet refined; stemming from personal impressions and experiences yet broadly accessible.

Related Posts: