Last Saturday I visited the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) to catch their exhibit Dance/Draw: an exploration of the influence of dance on artists, art created by dancers, or artists’ capturing of dance. Helen Molesworth, Chief Curator, writes in the exhibit introduction that the following works show “how artists and dancers have produced lines either as a gesture on a surface or as a movement in space.” The exhibit particularly focuses on work produced out of the influence of the Judson Dance Theater (1962-64) in downtown New York City, which stimulated the creation of anti-elitist, anti-establishment Postmodern dance emphasizing the incorporation of movements not traditionally considered “dance;” the absence of “emotional” expression; and the absence of conventional narrative.

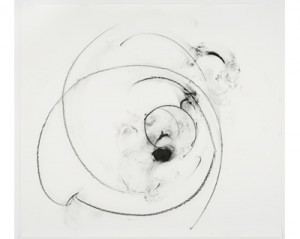

The exhibit first focuses on works that are impressions of gesture or bodies on paper, or that use the body as the drawing instrument itself–giving rise to the question asked by John Cage, “what is drawing?” Choreographer Trisha Brown creates large drawings by putting pieces of chalk or charcoal in between her toes, rubbing chalk on her feet and hands and smearing and pivoting across the surface of the paper (the curation calls these pieces “part self-portrait and part choreography”). The finished works imply rapid movement and circular, flowing gestures, but the live video of Brown shows that she is painstaking in her process.

In Butterfly Kisses (1996-99) and Loving Care (1992-96), Janine Antoni uses her body as a paintbrush–she coats paper with impressions of her mascara-coated eyelashes, and drags her ink-soaked hair along the floor of a gallery (taking Pollock’s “action painting” to the next level!). David Hammons created Body Print (1974) by making direct impressions of his face, clothing, and body on paper using grease.

Other artists in the exhibit focus on creating on an awareness of space that is somehow paralleled by or related to movement. Faith Wilding‘s Crocheted Environment, 1972/95, is a surreal, web-like space large enough for three people to stand in. The crocheted texture of the “walls” give the impression of a “drawing in air.” Drawing without Paper by Getrud Goldschmidt aka Gego (1984-7, enamel on wood and stainless steel wire) suggests the lines of an intricate drawing suspended in three dimensional space.

In addition to the themes of bodily gesture and space, a number of the artists in this exhibit engage with ideas of temporality: the temporariness of both dance and the artists’ creative process. I was particular intrigued by Daniel Ranalli’s Snail Drawings (1995-2011), in which Ranalli placed snails in spiral patterns on a beach and photographs the trails the snails produced in the sand as they crawled out of position. The photograph is all that’s left of this multi-process live event.

Tseng Kwong Chi, "Bill T. Jones Body Painting with Keith Haring," 1983. Silver gelatin selenium-toned print.

The exhibit also includes works that capture or reflect dance and dancers (photography, videos, figurative portraits). Tseng Kweng Chi‘s photographs of dancer/choreographer Bill T. Jones, sporting neo-tribal body painting by street artist Keith Haring, is an especially striking record of a collaboration between three artists. I was also intrigued by choreographer William Forsythe’s Lectures from Improvisation Technologies, 2011, an instructional film and a record of Forsythe’s technique. The filmmaker animates Forsythe’s movements by drawing lines to clarify his gestures–once again, dance is interpreted as drawing in the air.

The exhibit was accompanied by a live in-gallery performance of Trisha Brown’s 20-minute The Floor of the Forest, 1970, a piece that challenges definitions of dance, or performance art. In the piece, two dancers moved across a metal structure hung with empty, oversized clothing on ropes. The dancers alternatively take on and take off the pieces, hanging suspended about two feet off the floor, in articles of clothing–often in uncomfortable, contorted positions.